Wolves in North America

Wolf taxonomy has been an ongoing subject of debate. Some scientists and biologists argue that there are two species of wolf in North America (the Gray wolf and the Red wolf), while genomic research supports the idea that there are actually three distinct species: the Gray wolf, Red wolf, and the Eastern wolf. The Eastern wolf is recognized as a subspecies of Gray wolf.

The Gray Wolf (Canis lupus)

When one thinks of a wolf, the gray wolf (Canis lupus) is what comes to mind. At one time, there were at least 24 subspecies in North America recognized. Current classifications now divide them into 5 subspecies, which just means they vary in appearance or size depending on the region or habitats in which they live. As wolves move around, crossbreeding between subspecies does occur which can make identification more complicated. Names like "timber wolf" or "plains wolf" are simply a descriptive term on where they originate; it is still a gray wolf.

Subspecies currently recognized are the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), Arctic wolf (Canis lupus arctos), Great Plains wolf (Canis lupus nubilis), Rocky Mountain wolf (Canis lupus occidentalis), and the Eastern wolf (Canis lupus lyacon), but of course some consider them to be their own species (Canis lyacon). Eastern wolves are found in central Ontario and western Quebec, with a population of less than 500. The most endangered is the Mexican wolf subspecies, also known as the "lobo", which is found in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. There are less than 150 left in the wild.

The Red Wolf (Canis rufus)

The Red wolf is one of the most endangered canid species with less than 20 in the wild. They are reddish brown in color, with also some buff or black in their coats. On average, they range in size from about 45-80lbs. Like the Gray wolf, Red wolves live in family units that consist of the parents and their offspring. Red wolves mainly feed on small mammals or white tailed deer. The remaining wild wolves of this species live in North Carolina at the Alligator River Wildlife Refuge.

Historic Range, Eradication, and Current Range

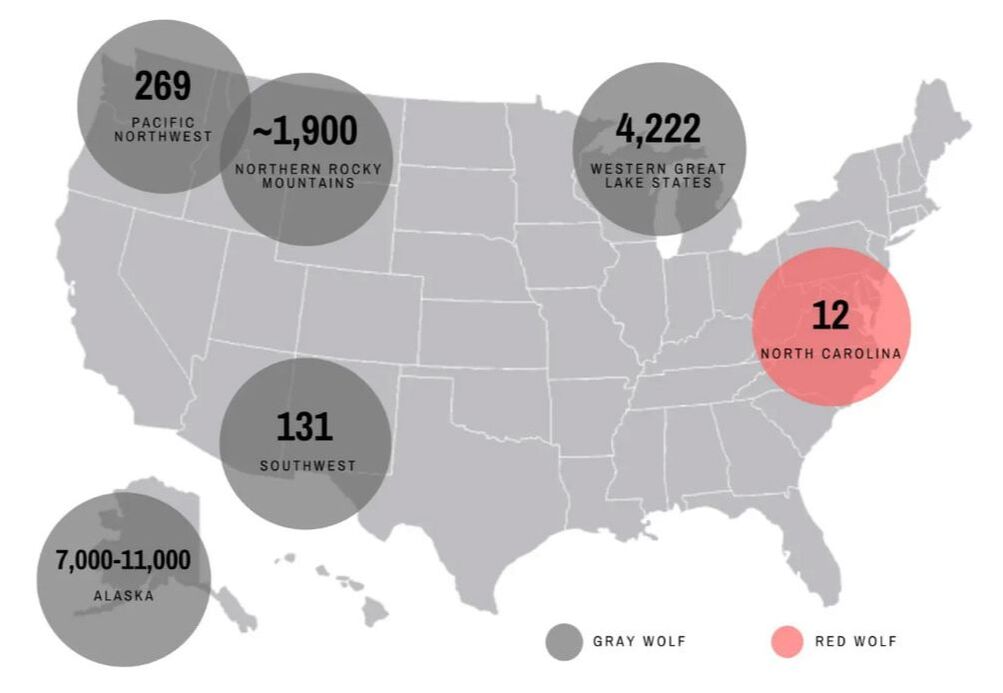

Maps from endangered.org and nywolf.org

The gray wolf was at one time found through most of North America, and red wolves primarily lived in the southeastern United States. By the 1930's however, the gray wolf was mostly exterminated by humans. Although Native Americans incorporated them into their culture, European settlers feared and hated these animals. The livestock they brought with them on settlements was left to roam freely- and were found by wolves to be easy meals. Fear and misunderstanding of wolves quickly led to hatred.

Wolf baiting and hunting became a common practice, and as early as 1877 poison was added to animal carcasses in Yellowstone in order to kill scavenging wolves. The pelts of wolves (and coyotes) were valuable which encouraged these activities. In the 19th century wealthy livestock farmers demanded wider range for their animals to graze, and complained that the land was "infested" with wolves. In 1906, the U.S. Forest Service enlisted the help of the Bureau to clear cattle ranges of gray wolves.

By the middle of the 20th century, government funded extermination had removed nearly all gray wolves in the lower 48. Even as late as the 1940's, the Bureau was still distributing anti-wolf propaganda. The future of wolves did not improve until the 1960's.

In 1973, wolves were given protection for the first time under the Endangered Species Act by congress. Most notably was the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone in 1995 and 1996 (the last wolves were killed in the park by rangers in 1926). Despite seeing many benefits of wolves and their positive impact on the ecosystem as an apex predator; anti-wolf views and attitudes continue, which contributes to the fact that they are constantly being stripped of protection across states.

Wolf baiting and hunting became a common practice, and as early as 1877 poison was added to animal carcasses in Yellowstone in order to kill scavenging wolves. The pelts of wolves (and coyotes) were valuable which encouraged these activities. In the 19th century wealthy livestock farmers demanded wider range for their animals to graze, and complained that the land was "infested" with wolves. In 1906, the U.S. Forest Service enlisted the help of the Bureau to clear cattle ranges of gray wolves.

By the middle of the 20th century, government funded extermination had removed nearly all gray wolves in the lower 48. Even as late as the 1940's, the Bureau was still distributing anti-wolf propaganda. The future of wolves did not improve until the 1960's.

In 1973, wolves were given protection for the first time under the Endangered Species Act by congress. Most notably was the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone in 1995 and 1996 (the last wolves were killed in the park by rangers in 1926). Despite seeing many benefits of wolves and their positive impact on the ecosystem as an apex predator; anti-wolf views and attitudes continue, which contributes to the fact that they are constantly being stripped of protection across states.

Size and Other Characteristics

- Depending on subspecies, gray wolves can range in weight from 50 to about 110lbs (with 110lbs considered to be very large) and about 26-36" tall at the shoulder. Females tend to be smaller.

- Their paws are about 4x5", or the size of an adult person's hand. They have long toes to help with running on a wide range of terrain, and webbed feet for swimming.

- Eye color ranges from yellow, brown, or even pale green.

- The fur of a gray wolf can range in color from white, black, red/brown tones, or many shades in between. They have a double coat which can keep them warm in temperatures as low as -45 C.

- An average lifespan of a wild wolf is about 3-6 years. In captivity, 12-15 is common.

Habitat and Diet

Wolves can thrive in a wide range of habitats including tundra, woodlands, forests, grasslands and deserts. In the United States, the gray wolf population ranges in Alaska, northern Michigan, northern Wisconsin, western Montana, northern Idaho, northeast Oregon and the Yellowstone area of Wyoming.

Hunting for food is a group effort. Wolves tend to eat large ungulates (such as deer, elk, bison, and moose) but will also pursue smaller game like rabbits or groundhogs. Despite claims that wolves decimate wild animal herds, they are only successful in taking down about 20% of the prey that they pursue, which equates to eating just once or twice a week. However, when they do take a kill they will gorge and can eat up to 20 pounds at a time. Other scavengers such as Ravens tend to follow the wolves and pick off of their kills.

Hunting for food is a group effort. Wolves tend to eat large ungulates (such as deer, elk, bison, and moose) but will also pursue smaller game like rabbits or groundhogs. Despite claims that wolves decimate wild animal herds, they are only successful in taking down about 20% of the prey that they pursue, which equates to eating just once or twice a week. However, when they do take a kill they will gorge and can eat up to 20 pounds at a time. Other scavengers such as Ravens tend to follow the wolves and pick off of their kills.

Family Life and Reproduction

|

A group, or 'family' of wolves is called a pack. Wolves rely on each other to survive, which is why they must live in family units rather than in pairs or alone. When it comes to their social structure, we are constantly learning new things about them. Recent studies suggest that labeling a wolf “alpha” or “omega” is misleading because “alpha” wolves are simply the parent wolves in a pack. Using the “alpha” term falsely suggests a rigidly forced permanent social structure, which has been disproven in wild packs. Even wolf biologist David Mech who coined the "alpha" term, has released a youtube video explaining why this is no longer scientifically accurate. Wolf packs average between 6-8 individuals but can be less or more. They will regulate their numbers based on how plentiful food is, and their territories can range from 50 square miles to over 1,000. Wolves will travel as far as they need to in order to find food. They often trot at five miles per hour but can reach speeds of about 35 miles per hour in short distances, typically when they are chasing prey.

Wolves are mature at 2 years old and when they choose a mate they breed with them for life. Only the breeding male and female have pups while other members of the pack contribute to raising them. Breeding season is typically late January through March, with the gestation period at 63 days. Litters have 4-6 pups who are born solid brown or black and weigh about one pound each. At birth, they are blind and deaf but open their eyes and ear canals within the first few weeks. Wild life is hard: pups grow quickly in order to be large enough to hopefully make it through their first winter. Only about 30% of pups survive past their first birthday. |

Communication

- Vocalizations

Howling is an important way for wolves to communicate. Wolves howl for many reasons: as a form of bonding, to contact separated members of their group, to mourn the loss of a pack member, to rally the pack before hunting, or to warn rival packs to stay away. Lone wolves will howl to attract mates or just because they are alone. Each wolf howls for only about five seconds, but howls can seem much longer when the entire pack joins in. Barking is rare, but can happen when one is startled. - Body Language

Like our domestic dog. wolves also communicate with body language which can also be combined with vocalizations to get their point across; everything from nibbling, licking, teeth baring, or posturing. The difference between wolf communication vs dogs is the intensity of the behavior; often body language is misinterpreted as aggression towards one another by individuals not used to observing wolf behaviors. - Scent

Wolves will mark their territories by using scat and urine, and can also identify individuals by the scent of their urine. They also have scent glands in their feet which can leave a trail behind after kicking up grass or dirt. Lastly, wolves will also roll in any interesting odors (called 'scent rolling') to cover their fur in it. It is thought they not only do this to cover their own scent, but also to bring back the smell to the pack to show what they have found.

Role in the Ecosystem

As a large apex predator, the presence of the wolf is essential to keep the ecosystem balanced and in check. Wolves hunt very young, old, or ill animals. This leaves the strongest and healthiest animals in the herd to breed and keep the population at a healthy number. Without the presence of the wolf, the ungulates become overpopulated and food sources for them and other herbivorous animals becomes scarce. Biologists saw many positive changes in Yellowstone National Park when wolves were introduced in the mid 90's. By reducing prey numbers, dispersing these animals on the landscape, and removing sick animals, wolves also may reduce the transmission and prevalence of wildlife diseases such as chronic wasting disease and brucellosis. In addition to improving wildlife herds, wolves have also altered the behavior of their prey, leading to beneficial effects on the landscape. In the absence of wolves, elk tended to browse heavily in the open flats along rivers and wetlands, since they did not need to evade predators by seeking thicker cover. Without fear of wolves, elk over-browsed the vegetation inhibiting the growth of new trees. Since the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone, elk spend more time in the safety of thick cover or on the move. Riparian areas and aspen groves that had been suppressed by decades of over-browsing are regenerating, improving habitat for species like beavers and songbirds. Beavers, which create wetland habitats with their dams, have improved water quality in streams by trapping sediment, replenishing groundwater, and cooling water. Species that rely on healthy riparian habitats and benefit from the presence of wolves in Yellowstone National Park include trout, moose, waterfowl, songbirds, small mammals and countless insects. We have learned that without wolves, the ecosystem suffers.

Myth and Fairytale

|

The "big bad wolf" is a widely recognized term. Wolves as characters in stories are always the villain. Humans have used the wolf in myth and fairy tales to teach lessons and instill fear in their children.

In reality, wolves are shy, skittish animals. They avoid strange or new situations out of fear, and will quickly run from a threat rather than rush towards it. There have been less than a half of a dozen documented cases of a wild wolf attacking a human, and in the instances that it did happen; the animals were sick. As a comparison, the domestic dog kills roughly 30 people per year. Our biggest mission is to disprove myths and remind the public that the stories about wolves are just that: stories. |